Representation Efficiency in Neural Reasoning–Evidence from Multilingual Mathematical Benchmarks

Published:

Authors: Bowen Yu, Linrui Ma, Yiwei Liang

1. Introduction

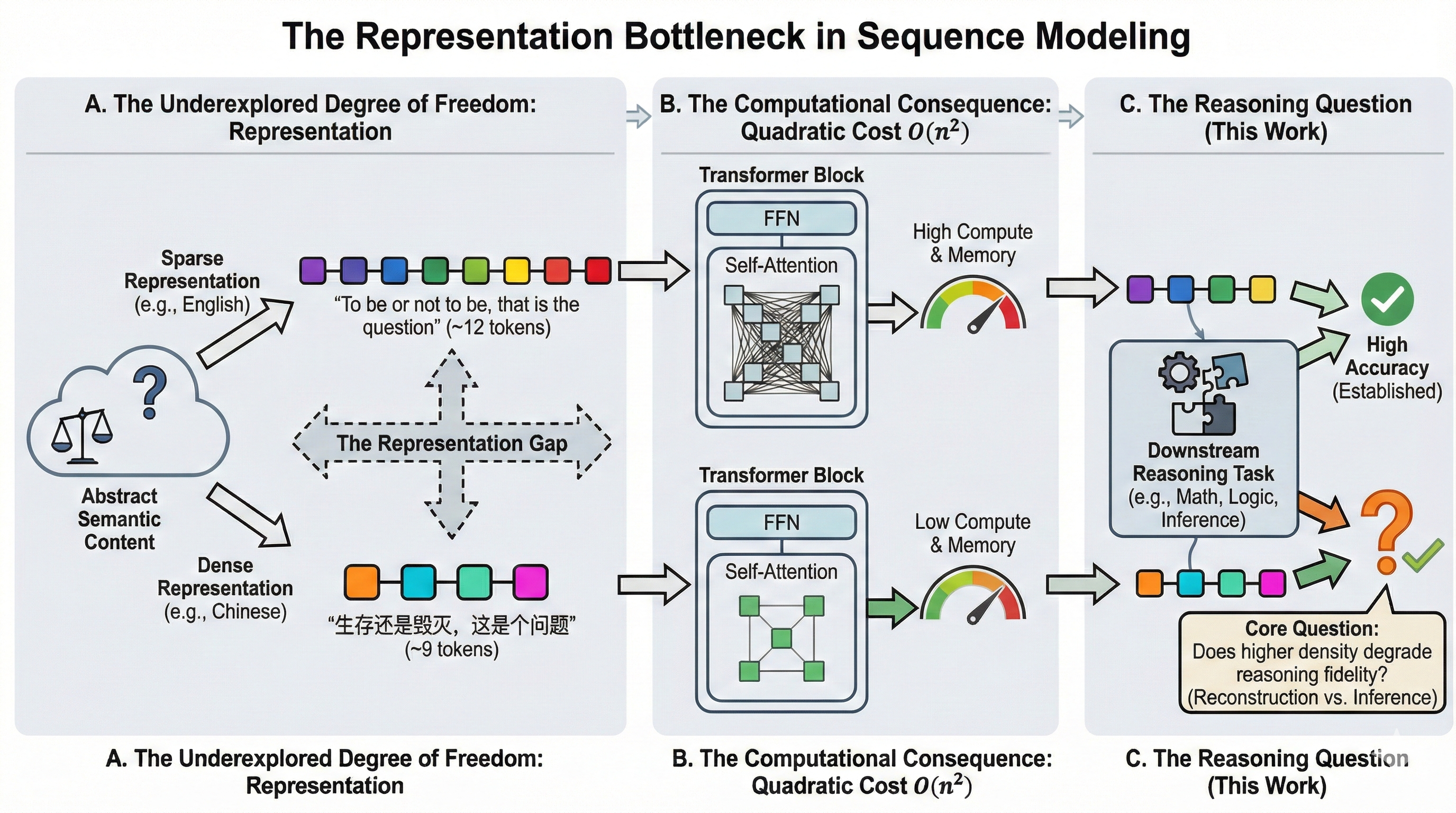

Sequence length constitutes a central bottleneck in modern deep learning. The Transformer architecture has become the dominant architecture in multiple domains, including language modeling, computer vision, and protein structure prediction. Yet, its efficacy is bound by a core limitation: the self-attention mechanism, which scales quadratically with sequence length, \(O(n^2 d)\). As a result, despite longer inputs usually help with richer context and more complex reasoning, they also suffer from slower and memory intensive inference.

Most work that tries to address this challenge focus on how a fixed sequence is processed. Sparse attention reduces the number of pairwise interactions. Learned compression tokens summarize context into a fixed number of vectors. Linear attention variants approximate self-attention to avoid quadratic scaling. In computer vision, patch pruning and latent-space compression pursue similar goals. All of these methods assume that the input representation is fixed, and efficiency must come from better algorithms rather than changing how the input is encoded.

But the way we encode information is itself a free design choice. The same content can show up as very different sequence lengths. An image might be split into 256 or 1024 patches. A protein can be described at the residue level or via larger structural motifs. A paragraph might use 100 tokens under one tokenizer and 60 under another. This means the representation already sets the token budget before any clever attention trick is applied.

This raises a key question: is performance limited by the representation we use, or just by the information it contains? If a model can solve the same task equally well when the input is encoded in 60 tokens instead of 100, then representation design becomes a direct knob for efficiency. If compressing the representation consistently hurts reasoning, then the trade-off between speed and accuracy is more rigid.

To investigate these questions, we utilize an experimental setting where the same semantic content naturally appears in representations of different lengths, so that we can vary sequence length without changing meaning. Natural language provides exactly this kind of setting. Different languages express the same idea with very different token counts. For example, “To be or not to be, that is the question” is roughly 12 tokens in English, while the Chinese version (“生存还是毁灭,这是个问题”) compresses to about 9 tokens under standard tokenizers. This difference is inherent to the languages rather than something we chose artificially.

Our experiments are organized around three questions. First, do well-trained models show representation-invariant reasoning? We choose to evaluate state-of-the-art (SOTA) models on multilingual math benchmarks to test whether accuracy depends on the particular linguistic representation or only on the underlying problem. Second, when performance does differ, is it due to the architecture or to the training data distribution? By comparing models trained on multilingual data with those trained primarily on English, we can separate architectural constraints from gaps in training coverage. Finally, if a model struggles with a denser representation, can a small amount of targeted fine-tuning close the gap? This tells us whether the bottleneck is baked into the architecture or mostly about optimization and coverage.

Our results show a consistent pattern. Representation choice clearly affects how many tokens are used, but it does not have to hurt reasoning as long as the model has been adapted to that representation. SOTA models can reach nearly the same accuracy across languages while using 5–10% fewer tokens in denser languages like Chinese. Models trained on narrower distributions show larger gaps at first, but modest fine-tuning recovers much of the lost performance. In practice, representation efficiency behaves less like a strict trade-off and more like a capability that can be unlocked with appropriate training.

Our findings extend beyond multilingual modeling. If reasoning performance is largely stable across different representation densities once models are adapted, then representation design should be treated as a first-class target for optimization. Instead of focusing only on more efficient attention mechanisms for fixed inputs, we can co-design models and representations that encode the same information in fewer tokens. Natural languages offer one family of such representations; learned compression schemes and domain-specific tokenizations offer others. Our work provides evidence and a concrete approach for studying how representation density interacts with reasoning fidelity, and for using representation design as a practical route to more efficient deep learning systems.

2. Related Work

Research into cost-effective sequence modeling generally fall into two catagories: speeding up how we process a fixed sequence of tokens, and changing the representation so that we start with fewer tokens in the first place.

2.1 Efficient Processing of Fixed Representations

The quadratic cost of self-attention has led to many architectural tricks for cutting compute while keeping performance. A major line of work focuses on sparse attention, as in Longformer 1 and BigBird 2. These models replace full attention with a mix of local windows, a few global tokens, and some random connections. This brings the complexity down from \(O(n^2)\) toward \(O(n)\) while still allowing information to move across the entire context. In practice, these ideas extend context length by about 4–8× on the same hardware and give noticeable gains on long-document tasks 2.

Other approaches reduce the number of tokens as the model runs. In vision transformers, Token Merging (ToMe) 3 repeatedly merges similar tokens across layers, speeding up inference without any task-specific finetuning. Joint Token Pruning and Squeezing 4 pushes this further by folding information from dropped tokens into the ones that remain, rather than discarding it. These results make a clear point: not all tokens matter equally. In some setups, cutting 95% of tokens only costs under 1% accuracy 5.

Linear-attention variants take a different route, approximating the softmax kernel so attention can be computed with associative matrix multiplications, again bringing complexity closer to \(O(n)\) 6. Across all of these methods, the input sequence is assumed fixed, and the goal is to process it more efficiently. This leaves open the question of whether we can instead redesign the representation itself to be more efficient.

2.2 Compact Representations Across Domains

A separate line of work asks whether we can encode the same information more compactly before it ever reaches the transformer.

Autoencoders and variational autoencoders 7 are classical examples. They learn to compress high-dimensional inputs into low-dimensional latent spaces. Their behavior is well described by the rate-distortion trade-off, where aggressive compression reduces bitrate but introduces reconstruction error following predictable information-theoretic curves 8. In learned image compression, neural networks now rival classical codecs by learning latent representations that are explicitly optimized for reconstruction quality 9, achieving 10–20× compression while keeping perceptual quality high 10. The key insight is that learned encodings can exploit statistical structure in data far better than hand-designed schemes.

However, a key gap remains between these compression studies and the need of large reasoning models. Most compression work targets reconstruction, where the objective is to faithfully recover the input signal. It is still unclear to what extent compact representations preserve the information necessary for reasoning, rather than just for signal recovery.

Our work targets this gap by treating natural languages as a family of representations with different inherent information densities. Instead of designing a new compression model, we fix the underlying task and vary only the linguistic encoding, asking whether shrinking the token budget compromises reasoning performance or offers a viable path toward representation-level efficiency.

3. Experimental Setup

We design three experiments to progressively investigate how representation density affects reasoning quality: evaluating SOTA models for baseline representation invariance, comparing models with different training distributions to reveal potential bottlenecks, and fine-tuning to test whether such bottlenecks are learnable.

3.1 Datasets

We use two mathematical reasoning benchmarks that provide semantically equivalent problems across languages. MMATH is a multilingual benchmark comprising 374 competition-level mathematics problems sourced from AIME and CNMO, professionally translated into 10 languages including English, Chinese, Spanish, and Thai. The difficulty level ensures that problems require multi-step reasoning rather than pattern matching. GSM8K consists of 1,319 grade-school math word problems in its test set. Since no official Chinese version exists, we translated the dataset using GPT-5.1-mini and manually verified 100 randomly sampled examples to confirm translation fidelity. The training split (7,473 examples) serves as the basis for our fine-tuning experiments.

3.2 Models

Our experiments span three categories of models. For SOTA evaluation, we use three frontier API models: ChatGPT-5.1, Gemini-2.5-Flash, and DeepSeek-V3.2. These models represent the current capability frontier and have been trained on massive multilingual corpora, making them suitable for testing whether well-trained models achieve representation-invariant reasoning.

For controlled comparison, we evaluate two open-source 8B-parameter models with contrasting training distributions: Qwen3-8B, which emphasizes multilingual capability, and Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct, which is predominantly English-centric. This pairing allows us to isolate the effect of training distribution while controlling for model scale.

For fine-tuning experiments, we adapt Llama-3.1-8B on the Chinese GSM8K training set using Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) with rank 32 and \(\alpha=64\), targeting all attention and MLP projection matrices. Training proceeds for 500 steps with learning rate \(10^{-5}\) and gradient accumulation over 2 steps. This lightweight adaptation tests whether representation bottlenecks can be overcome with modest additional training.

3.3 Evaluation Protocol

All models receive problems formatted with language-appropriate prompts instructing step-by-step reasoning and a final numerical answer in the format #### <number>. We extract answers via regex matching and evaluate exact numerical correctness.

For SOTA models on MMATH, we use a maximum token budget of 8,192 and evaluate across four languages (English, Chinese, Spanish, Thai). For open-source models on GSM8K, we sweep maximum token budgets from 128 to 4,096 to analyze accuracy as a function of generation length, revealing how quickly models converge to their peak performance in each representation. More detailed configurations can be found in the appendix.

3.4 Token Length Analysis

To measure representation efficiency independent of any single tokenizer’s biases, we tokenize model outputs using five different tokenizers: Qwen3-8B, DeepSeek-V3, Seed-Coder-8B, Llama-3.1-8B, and GPT-4o (via tiktoken). For fair comparison, we restrict analysis to problems where the model answered correctly in both English and Chinese, ensuring we compare token counts for successful reasoning chains rather than failed attempts. We report the ratio of Chinese to English token counts, where values below 1.0 indicate that Chinese uses fewer tokens for equivalent reasoning.

4. Results and Analysis

We present findings from three experiments that progressively investigate the relationship between representation choice and reasoning quality. Our results support the thesis that representation density affects token efficiency but not necessarily task performance, when the model has been adequately trained on the target representation. Crucially, we distinguish between intrinsic density (information per character) and realized density (information per token), showing that the gap between them. We call this the Encoder Gap, that determines whether theoretical efficiency translates to computational savings.

4.1 SOTA Models Exhibit Representation-Invariant Accuracy

Our first experiment evaluates whether well-trained frontier models achieve similar reasoning accuracy across representations encoding the same mathematical content. We hypothesize that, if reasoning quality depends only on information content rather than representation format, the accuracy should remain stable across representations while output lengths vary with intrinsic density.

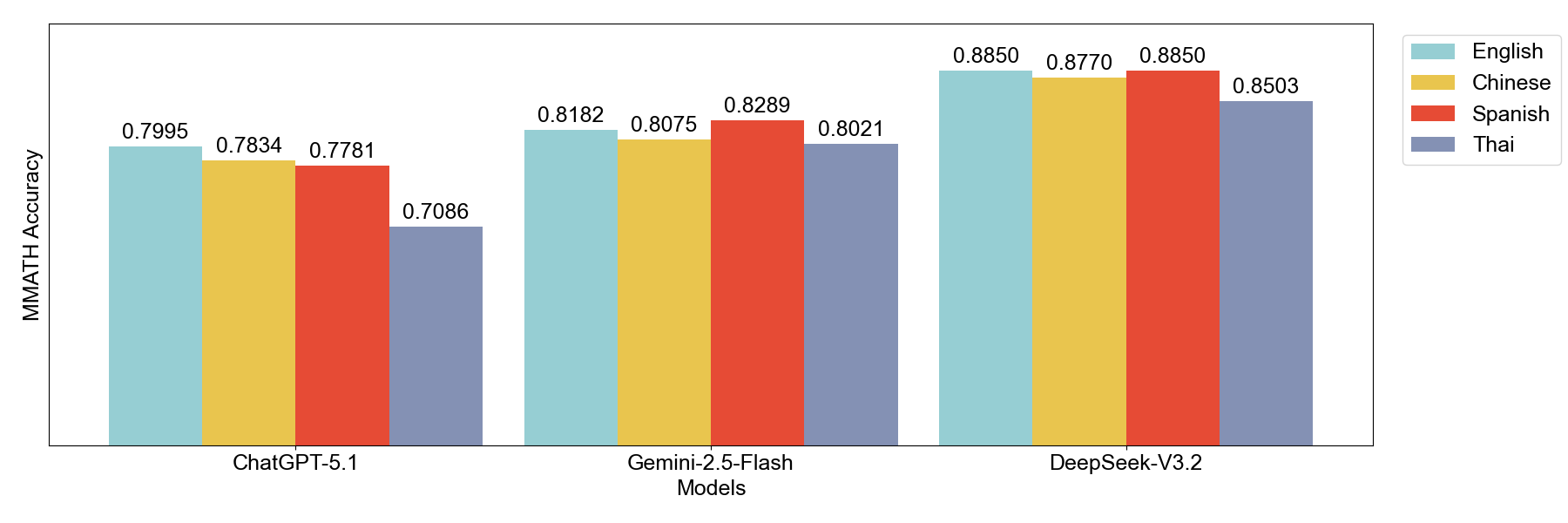

Accuracy Results. Table 1 presents accuracy on MMATH across four languages for three frontier models. ChatGPT-5.1 achieves 80.0% accuracy on English and 78.3% on Chinese, with a gap of merely 1.7 percentage points. DeepSeek-V3.2 shows even stronger representation invariance, with English at 88.5% and Chinese at 87.7% (0.8% gap). Across all three models, the maximum accuracy gap between any two languages remains under 10 percentage points.

| Model | English | Chinese | Spanish | Thai |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChatGPT-5.1 | 80.0% | 78.3% | 77.8% | 70.9% |

| Gemini-2.5-Flash | 81.2% | 80.8% | 82.9% | 80.2% |

| DeepSeek-V3.2 | 88.5% | 87.7% | 88.5% | 85.0% |

These results confirm that sufficiently trained models achieve nearly equivalent reasoning performances across different linguistic representations that encode the problem. The small gaps that do exist likely reflect residual differences in training data coverage rather than fundamental representation limitations. This establishes a critical premise: for well-trained models, the “semantic latent space” is stable. The model has learned to decouple meaning from encoding.

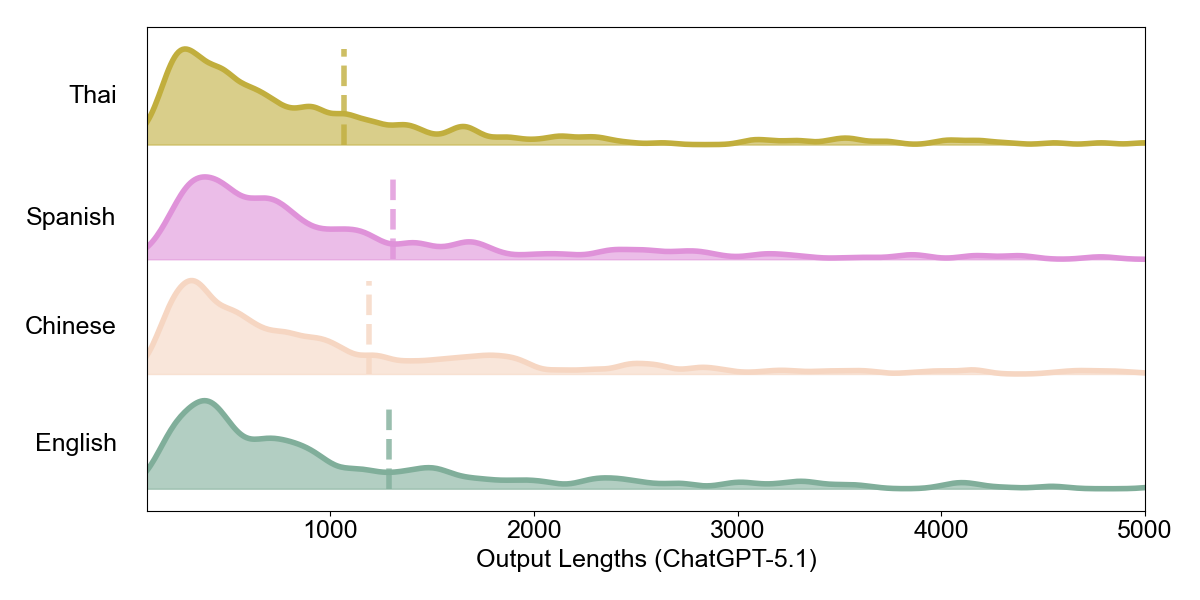

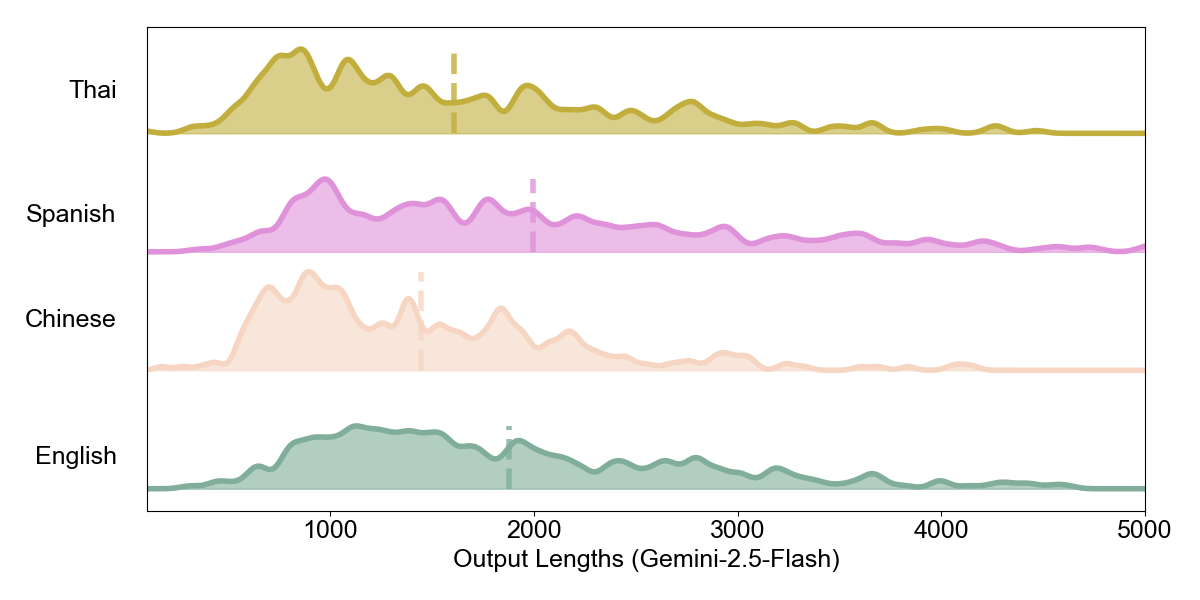

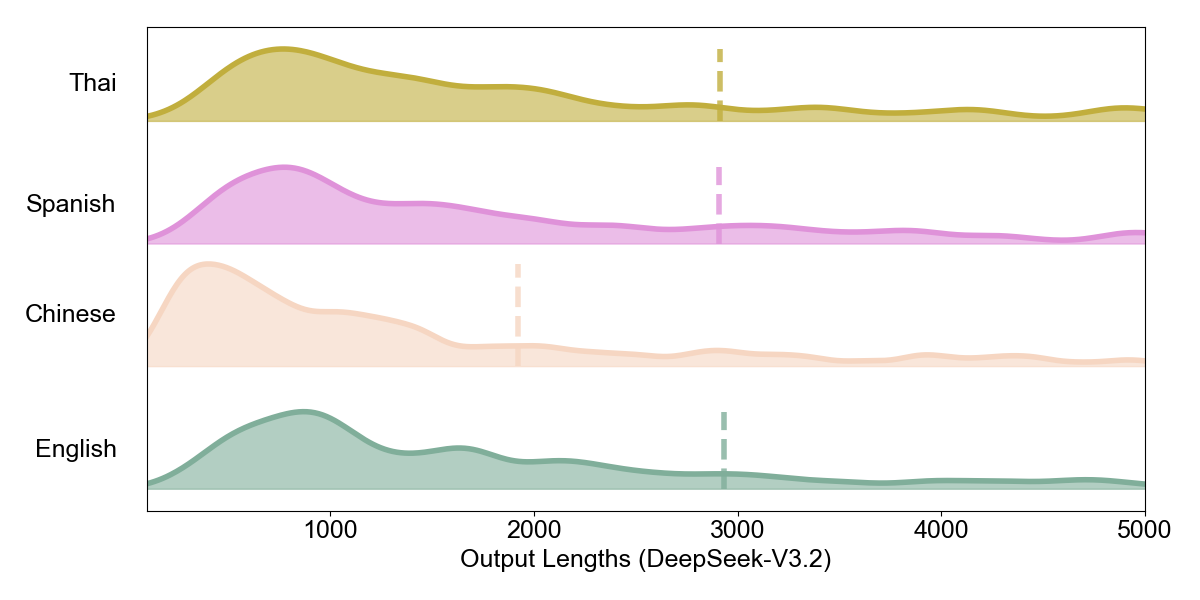

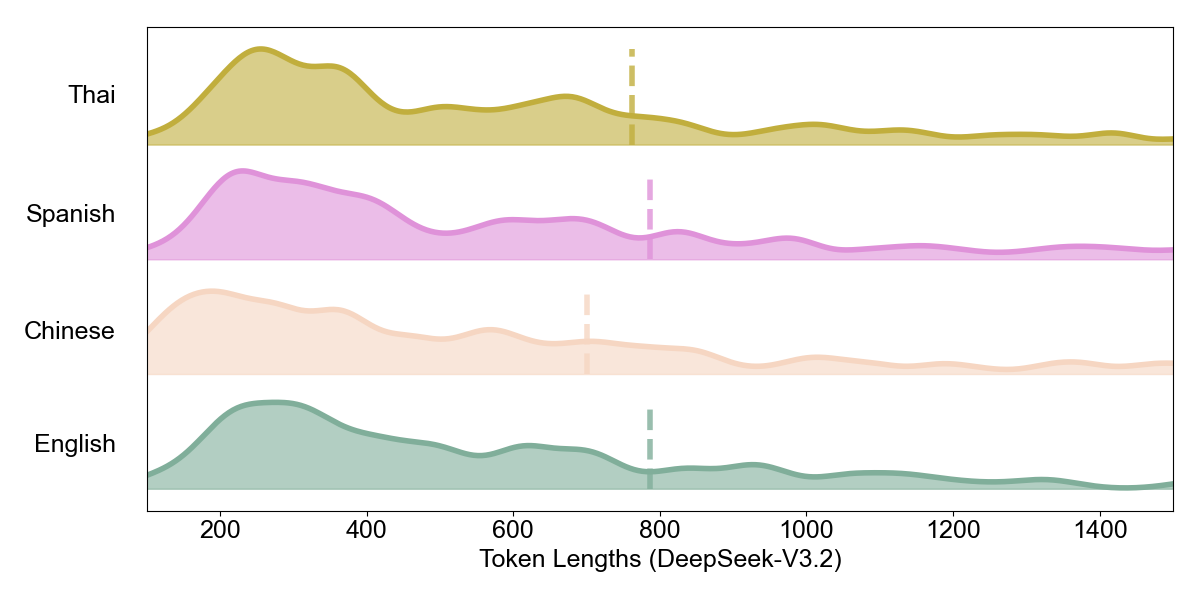

Intrinsic Density: Character-Level Analysis. Having established reasoning invariance, we examine whether different representations exhibit different intrinsic densities. Figures 5–7 show the distribution of raw output character lengths across languages.

A notable pattern emerges: DeepSeek-V3.2 produces substantially shorter Chinese outputs at the character level compared to English, while ChatGPT-5.1 and Gemini-2.5-Flash show more similar distributions across languages. Chinese, as a logographic writing system, naturally encodes more information per character than alphabetic scripts.

Yet whether models exploit this intrinsic density varies. DeepSeek generates concise Chinese outputs, while ChatGPT and Gemini do not leverage this compactness to the same degree. This difference in generation verbosity foreshadows the divergence we observe at the token level.

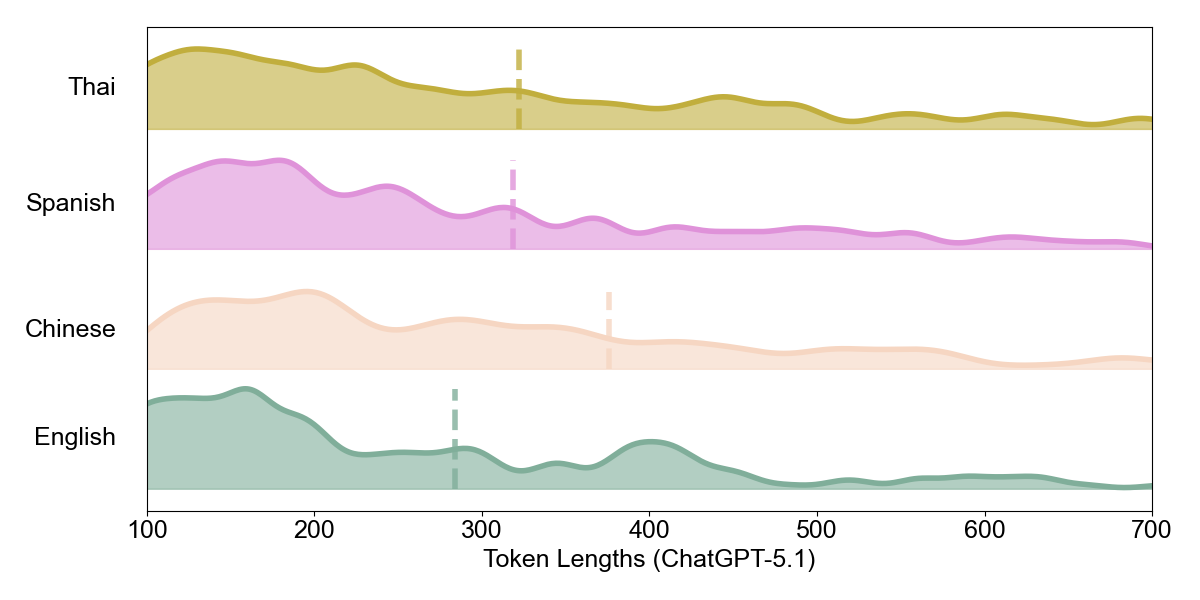

Realized Density: Token-Level Analysis. The central question is whether intrinsic density translates to computational savings. We define realized density as information per token. It is the actual sequence length processed by the Transformer, which determines the computational cost via attention’s \(O(n^2)\) complexity.

Here we observe a critical divergence:

Alignment (DeepSeek-V3.2): The model translates intrinsic density into realized density. Average output token length drops from 786.4 tokens in English to 700.7 tokens in Chinese, reduced by 11%. Chinese uses the fewest tokens among all four languages, directly reducing computational cost.

Inversion (ChatGPT-5.1, Gemini-2.5-Flash): These models exhibit “density inversion.” Despite Chinese being intrinsically denser, Chinese outputs require 33% more tokens (ChatGPT) and 40% more tokens (Gemini) than English. The theoretical efficiency advantage becomes a practical liability.

| Model | EN Tokens | ZH Tokens | ZH/EN Ratio | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSeek-V3.2 | 786.4 | 700.7 | 0.89 | Aligned |

| ChatGPT-5.1 | 282.6 | 375.8 | 1.33 | Inverted |

| Gemini-2.5-Flash | 360.5 | 503.8 | 1.40 | Inverted |

The Encoder Gap. This divergence isolates the Encoder Gap, which is the discrepancy between intrinsic and realized density. For DeepSeek, the tokenizer (and model training) preserves the density advantage: fewer characters \(\rightarrow\) fewer tokens. For ChatGPT and Gemini, the encoding is inefficient: the tokenizer fragments the dense Chinese signal into more tokens, or the model generates more verbose outputs, negating the representation’s inherent compactness.

To quantify this independent of any single model’s tokenizer, we re-tokenized DeepSeek-V3.2’s outputs (problems correct in both EN and ZH, \(N=321\)) using five different tokenizers:

| Tokenizer | Avg EN Tokens | Avg ZH Tokens | ZH/EN Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSeek-V3 | 823.6 | 748.3 | 0.909 |

| Seed-Coder-8B | 941.5 | 858.6 | 0.912 |

| Qwen3-8B | 904.9 | 847.9 | 0.937 |

| GPT-4o | 866.2 | 811.5 | 0.937 |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 860.1 | 813.3 | 0.946 |

All five tokenizers show ZH/EN ratios below 1.0 (5–9% savings), confirming that DeepSeek’s Chinese outputs are genuinely more compact. The variation in ratios (0.91–0.95) reflects differences in tokenizer vocabulary coverage for Chinese.

Implications. This finding has direct computational implications. When a model is aligned (producing concise outputs in dense representations and using a tokenizer that preserves that density) inference costs scale proportionally with representation choice. The same reasoning quality at 11% reduced token count yields savings in attention computation. However, when misaligned, choosing a “denser” representation can increase costs. Representation efficiency is not automatic; it requires encoder-representation alignment.

4.2 Training Distribution Determines Representation Capability

Our second experiment tests whether representation invariance is a property of model architecture or training distribution. We compare two 8B-parameter models with contrasting training emphases: Qwen3-8B and Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct. According to official documentation, Qwen3-8B was trained on 36 trillion tokens spanning 119 languages with explicit support for over 100 languages including Chinese 11. In contrast, Meta’s Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct officially supports only eight languages: English, German, French, Italian, Portuguese, Hindi, Spanish, and Thai. Notably, Meta explicitly stated that Llama 3.1 has been trained on a broader collection of languages than the 8 supported languages, but developers must fine-tune for unsupported languages, such as Chinese, for better performance 12. Thus, the contrast between the two models allows us to isolate the effect of training distribution while controlling for model scale.

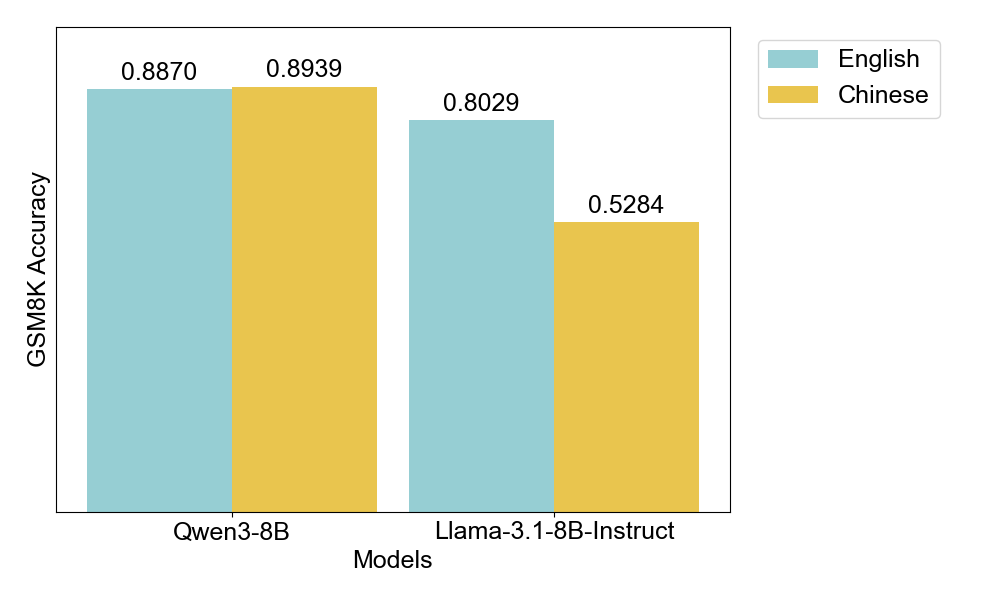

Contrasting Performance Profiles. On GSM8K, Qwen3-8B achieves 88.7% accuracy on English and 89.4% on Chinese (max tokens = 4096). These performances across representations are essentially identical. This aligns with the representation invariance we observed in SOTA models in Section 4.1. However, the results diverge sharply for Llama-3.1-8B: 80.3% on English but only 52.8% on Chinese, a gap of 27.5 percentage points.

| Model | English | Chinese | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qwen3-8B | 88.7% | 89.4% | +0.7% |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 80.3% | 52.8% | −27.5% |

This stark contrast reveals that the performance gap is not intrinsic to the Chinese representation. If it were, Qwen would also struggle. Instead, Llama’s performance decline reflects its insufficient exposure to Chinese during training. The representation itself supports effective reasoning; the model simply hasn’t learned to exploit it.

Per-Question Consistency Analysis. To further examine this phenomenon, we analyzed per-question consistency across the two languages. For each of the 1,319 test problems, we recorded whether the model answered correctly in English, Chinese, both, or neither.

| Model | Both Correct | EN Only | ZH Only | Both Wrong |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qwen3-8B | 1,088 (82.5%) | 82 (6.2%) | 91 (6.9%) | 58 (4.4%) |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 613 (46.5%) | 446 (33.8%) | 84 (6.4%) | 176 (13.3%) |

The results are striking. Llama answers 446 questions (33.8%) correctly in English but incorrectly in Chinese. These are problems where the model demonstrably possesses the mathematical knowledge but fails to apply it when the problem is presented in Chinese. A representative instance:

Problem: There are four schools competing at a basketball tournament. Each school has sent a girls’ basketball team and a boys’ basketball team and each team has 5 players each. Each school has also sent a coach for each team. In total, how many people have all of the schools sent?

Chinese Version: “有四所学校参加篮球锦标赛。每所学校均派出一支女子篮球队和一支男子篮球队,每队有 5 名球员。每所学校还为每支队派出一名教练。总共这些学校一共派出了多少人?”

Gold Answer: 48

English Output (Correct): The model correctly reasons: “Each team has 5 players and 1 coach, so 6 people per team. Each school sends 2 teams (girls’ and boys’), so 12 people per school. With 4 schools, the total is 4 × 12 = 48.”

Chinese Output (Incorrect): The model miscounts: “每所学校派出了两支球队,每支球队有5名球员,所以每所学校派出了10名球员。每所学校还有一名教练,总共 1 名。” (Each school sent 2 teams with 5 players each, so 10 players per school. Each school also has one coach, totaling 1.) The model treats “a coach for each team” as one coach per school rather than one per team, arriving at 11 people per school and 44 total.

This example illustrates a systematic failure mode: the model understands the mathematical structure when presented in English but misparses the same logical relationship (“a coach for each team” → 2 coaches per school) when the problem is presented in Chinese. The mathematical capability is conserved; only the representation-specific parsing fails.

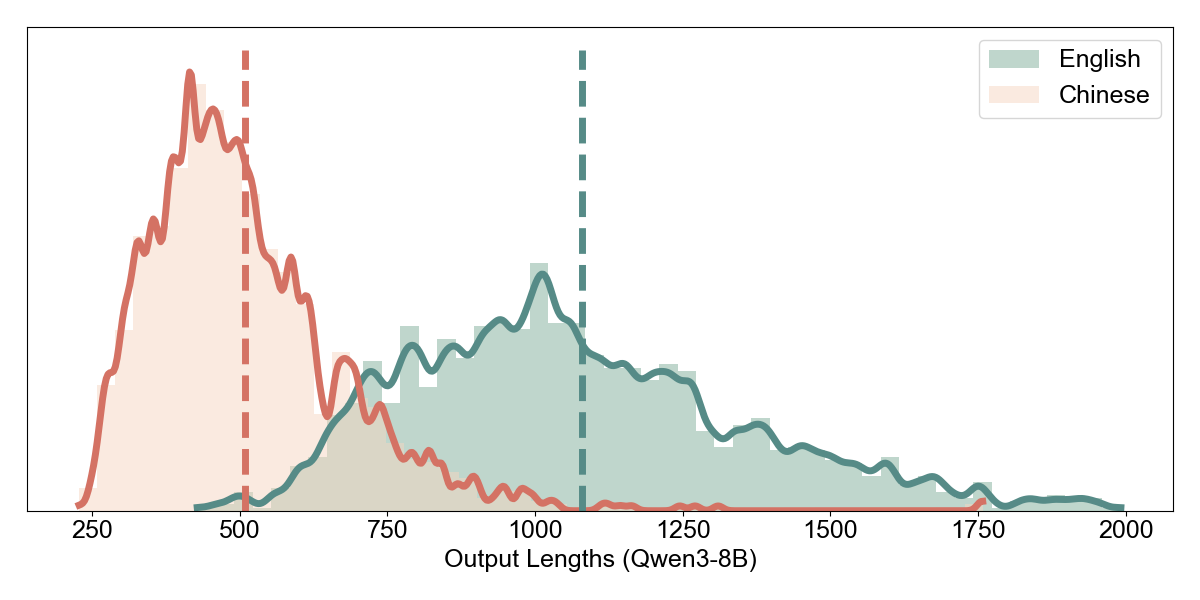

Accuracy vs. Token Budget. We examined how accuracy scales with maximum token allowance. For Qwen3-8B, both languages reach near-peak accuracy by 512 tokens (EN: 88.1%, ZH: 90.7%), with Chinese actually converging slightly faster. This suggests that denser representations complete reasoning in fewer tokens without sacrificing quality.

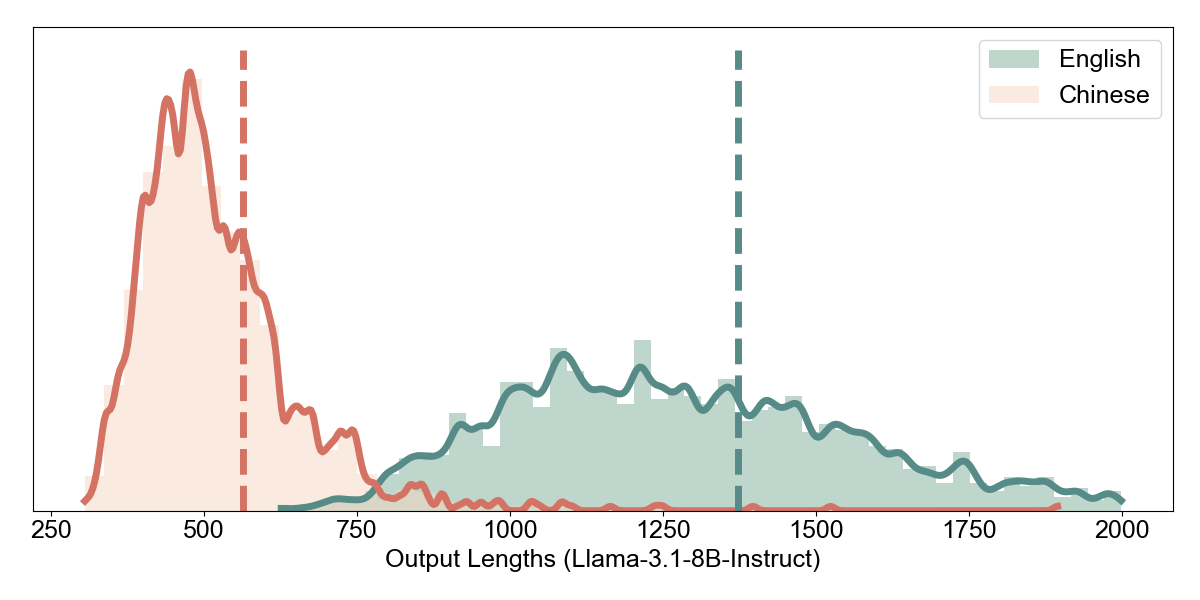

Llama-3.1-8B shows a different pattern: English accuracy climbs steadily from 4.6% (128 tokens) to 80.3% (512+ tokens), while Chinese plateaus at 52.8% regardless of additional token budget. The bottleneck is not token availability but the model’s inability to reason effectively in the Chinese representation.

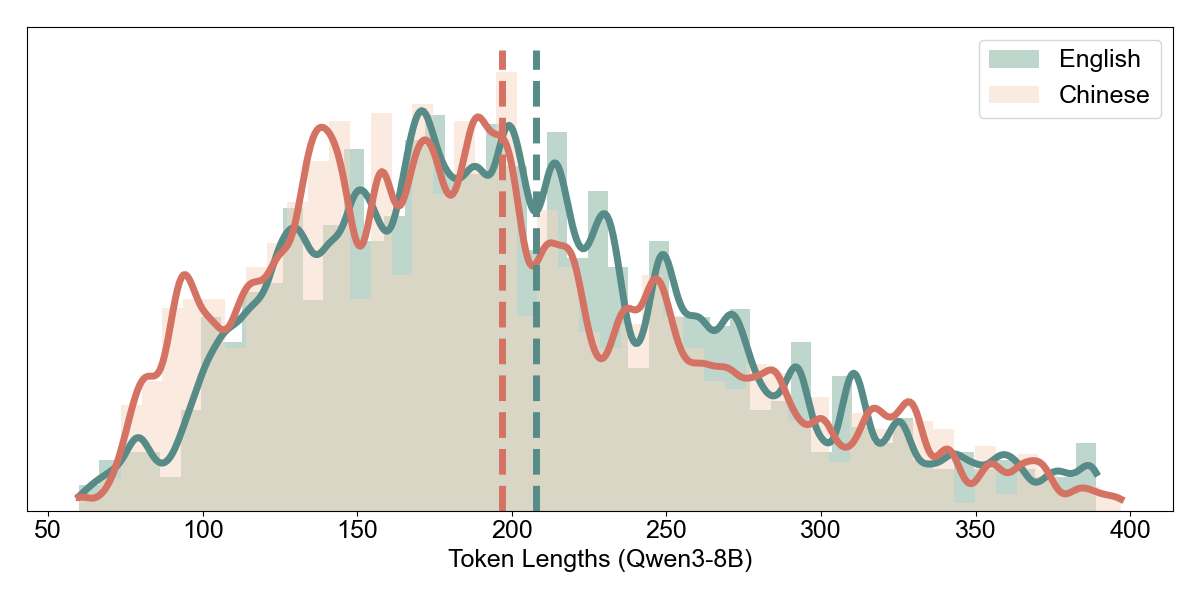

Intrinsic Density: Character-Level Analysis. Paralleling our analysis in Section 4.1, we examine whether the intrinsic density advantage of Chinese manifests in the open-source models’ outputs. For the 1,088 problems where Qwen3-8B answered correctly in both languages, Chinese outputs average 314 characters compared to 616 for English, which is reduced by 49% (ZH/EN ratio = 0.51). This confirms that Chinese is intrinsically denser: the model expresses equivalent reasoning in roughly half the characters.

This pattern is consistent with what we observed for DeepSeek-V3.2 on MMATH (Section 4.1), where Chinese outputs were ~35% shorter at the character level. Both well-trained models, Qwen and DeepSeek, produce concise Chinese outputs that exploit the representation’s intrinsic density.

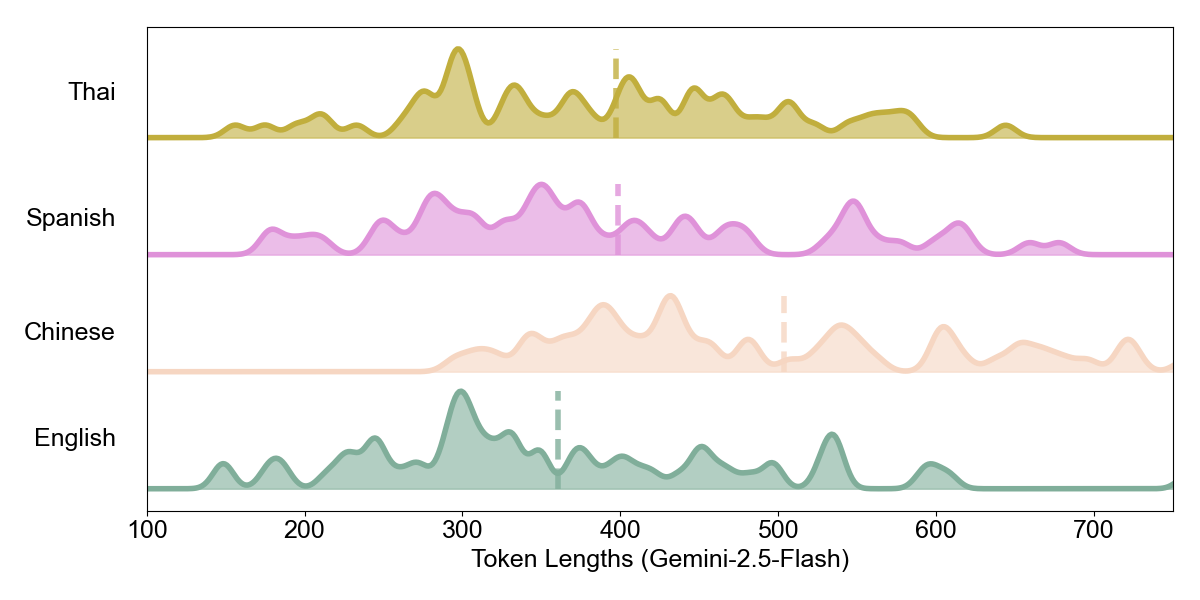

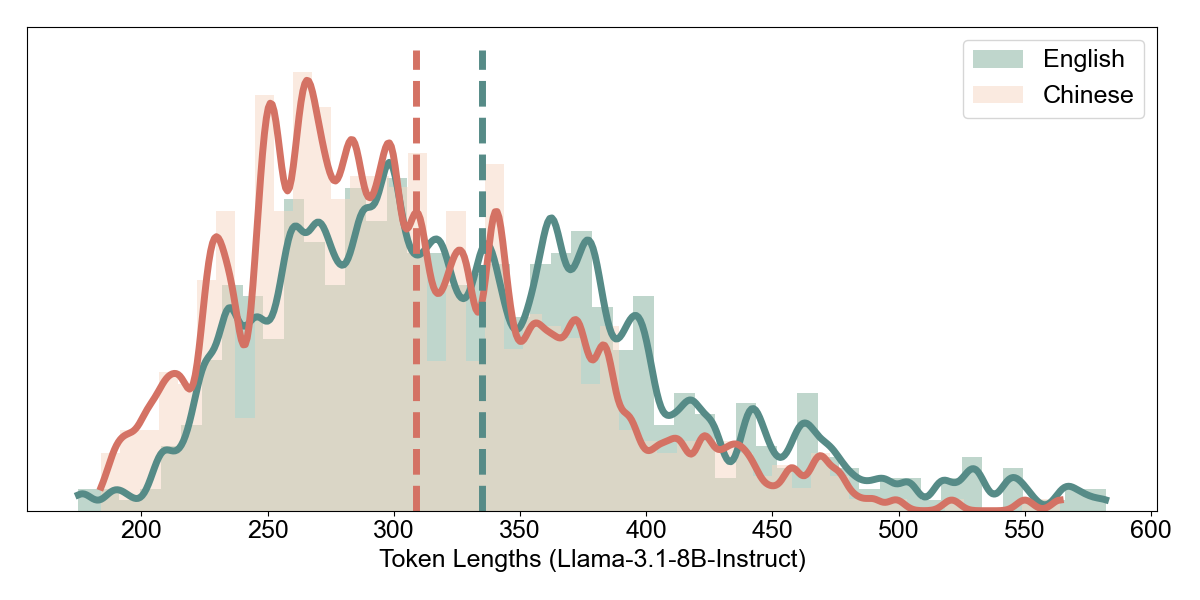

Realized Density: Token-Level Analysis. The critical question, as established in Section 4.1, is whether intrinsic density translates to realized efficiency. We re-tokenized Qwen3-8B’s outputs using five different tokenizers:

| Tokenizer | Avg EN Tokens | Avg ZH Tokens | ZH/EN Ratio | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSeek-V3 | 288.4 | 258.9 | 0.898 | Aligned |

| Seed-Coder-8B | 325.0 | 303.1 | 0.933 | Aligned |

| Qwen3-8B | 308.4 | 296.4 | 0.961 | Aligned |

| GPT-4o | 292.9 | 297.0 | 1.014 | Inverted |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 294.1 | 303.7 | 1.033 | Inverted |

A striking pattern emerges that directly parallels our MMATH findings:

Multilingual-optimized tokenizers (DeepSeek, Seed-Coder, Qwen) preserve the density advantage: Chinese uses 4–10% fewer tokens than English.

English-centric tokenizers (GPT-4o, Llama) exhibit density inversion: despite Chinese being 49% shorter at the character level, it requires the same or more tokens after encoding.

This is the Encoder Gap in action. Llama’s tokenizer, optimized for English, fragments Chinese text inefficiently. Each Chinese character may require multiple tokens, destroying the intrinsic density advantage. The same reasoning, expressed more compactly in Chinese characters, balloons back to equivalent (or greater) token counts after encoding.

The Compounding Effect. For Llama-3.1-8B, the Encoder Gap compounds its training gap. Not only does the model struggle to reason in Chinese (accuracy: 52.8% vs 80.3%), but even when it succeeds, it gains no efficiency benefit. Chinese outputs require more tokens (ratio = 1.033) despite being intrinsically denser. The model pays a “Tokenizer Tax” on top of its capability gap.

In contrast, Qwen3-8B demonstrates what aligned representation efficiency looks like: near-identical accuracy across languages (88.7% vs 89.4%) combined with genuine token savings (4–10% depending on tokenizer). The model has learned to exploit the dense representation, and multilingual tokenizers preserve that advantage.

4.3 Representation Bottlenecks Are Learnable

Our third experiment asks whether Llama’s Chinese performance gap can be closed through targeted fine-tuning. If the bottleneck reflects training distribution rather than architectural limitation, then additional exposure to Chinese reasoning should improve performance.

Fine-tuning Setup. We fine-tuned Llama-3.1-8B on the Chinese GSM8K training set (7,473 examples) using LoRA for 500 steps. This represents a modest intervention, approximately 0.1% of pretraining compute.

Results. Fine-tuning on Chinese data yields substantial improvements:

| Model | English | Chinese | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Llama (base) | 80.3% | 52.8% | −27.5% |

| Llama (ft-zh) | 81.1% | 61.6% | −19.5% |

Chinese accuracy improves by 8.8 percentage points (52.8% → 61.6%) while English performance is maintained (slight improvement to 81.1%). The EN-ZH gap narrows from 27.5% to 19.5%. Notably, fine-tuning on Chinese does not degrade English performance, suggesting the model acquires new representation capabilities without forgetting existing ones.

Interpretation. These results demonstrate that representation bottlenecks are learnable rather than architectural. A model that initially struggles with a denser representation can acquire competence through targeted exposure. This has practical implications: rather than accepting representation-dependent performance as fixed, practitioners can adapt models to work effectively with more efficient representations.

The persistence of a 19.5% gap after fine-tuning suggests that 500 steps of LoRA adaptation captures much but not all of the capability gap. More extensive fine-tuning or full-parameter training would likely narrow the gap further. Nevertheless, the experiment establishes the key finding: representation capability is malleable.

4.4 Summary of Findings

Our experiments yield three key insights, unified by the framework of intrinsic versus realized density:

Reasoning is representation-invariant for well-trained models. SOTA models exhibit near-identical accuracy across languages (<2% gap for ChatGPT, DeepSeek; <1% for Qwen). The model’s “semantic latent space” is stable, as it has learned to decouple meaning from encoding.

Intrinsic density does not guarantee realized efficiency. Chinese is ~35–50% denser at the character level, but this advantage is preserved only when the encoder (tokenizer) and model training are aligned with the representation. DeepSeek and Qwen achieve 5–10% token savings with multilingual tokenizers; ChatGPT and Gemini show 33–40% token penalties; English-centric tokenizers (Llama, GPT-4o) exhibit density inversion even on well-formed outputs. The Encoder Gap determines whether theoretical efficiency becomes practical savings.

Training distribution determines representation capability, and bottlenecks are learnable. Models with narrow training distributions (Llama on Chinese) show degraded performance that models with broader training (Qwen) do not. However, modest fine-tuning substantially improves performance on underrepresented representations without degrading capability on well-supported ones.

Together, these findings support treating representation choice as a first-class design variable, but with an important qualification. Realizing efficiency gains from dense representations requires alignment across three layers: (1) choosing representations with high intrinsic density, (2) using tokenizers that preserve that density, and (3) training models that exploit rather than waste the density advantage. When all three layers are aligned, denser representations offer genuine efficiency gains at no accuracy cost. When misaligned, the theoretical advantage becomes a practical liability.

5. Conclusion

We set out to investigate whether representation choice affects reasoning quality, or only the token budget required to achieve it. Using natural languages as semantically-aligned representations of varying density, we evaluated mathematical reasoning across multiple models, languages, and experimental conditions. Our findings consistently support the thesis that representation efficiency and reasoning quality are separable concerns. Denser representations reduce token counts without degrading accuracy, provided models have been adequately trained.

Three key results emerge from our experiments. First, SOTA models exhibit representation-invariant reasoning: ChatGPT-5.1 and DeepSeek-V3.2 achieve near-identical accuracy across English and Chinese (gaps under 2%) while Chinese outputs require 5–9% fewer tokens. The same mathematical content, encoded more compactly, yields equivalent reasoning at reduced computational cost. Second, representation capability reflects training distribution rather than architectural limitation. Llama-3.1-8B’s 27.5% accuracy gap on Chinese versus English disappears in Qwen3-8B, which was trained on more balanced multilingual data. The bottleneck is not intrinsic to the representation or the architecture—it is an artifact of training. Third, representation bottlenecks are learnable. Modest fine-tuning (500 steps of LoRA) improves Llama’s Chinese accuracy by 8.8 percentage points while preserving English performance, demonstrating that models can acquire new representation capabilities without catastrophic forgetting.

These findings reframe efficiency in deep learning. The dominant approach, which optimizes how we process fixed representations, addresses only half the problem. Our results suggest a complementary strategy: optimizing the representation itself. When denser encodings preserve reasoning quality, choosing them yields efficiency gains that compound with scale and require no architectural modification.

Several directions merit future investigation. Extending our analysis beyond mathematical reasoning to code generation, logical inference, and open-ended tasks would test the generality of representation invariance. Studying whether models can learn to translate inputs into more efficient representations before reasoning, and whether this end-to-end pipeline yields net efficiency gains, could yield practical inference optimizations. Finally, investigating tokenizer design through the lens of representation efficiency may reveal opportunities to learn encodings that are simultaneously compact and reasoning-friendly.

More broadly, our work contributes to a shift in perspective: from treating tokenization as a preprocessing detail to recognizing representation choice as a first-class design variable. Natural languages offer one family of representations with varying efficiency; learned compression schemes, structured encodings, and domain-specific tokenizations offer others. As models scale and inference costs grow, the question of how to encode information, not just how to process it, becomes increasingly central to efficient deep learning.

Appendix

A.1 Translation Quality Verification

The Chinese GSM8K dataset was created by translating the original English GSM8K using GPT-5.1-mini. To verify translation quality, we randomly sampled 100 examples and manually reviewed them for semantic fidelity, numerical accuracy, and grammatical correctness.

Verification Criteria:

- Semantic fidelity: The mathematical problem preserves its original meaning and all relevant details

- Numerical accuracy: All numbers, units, and mathematical relationships are correctly preserved

- Grammatical correctness: The Chinese translation is natural and grammatically correct

Results: Of the 100 sampled translations, 98 were deemed fully accurate, with 2 containing minor phrasing issues that did not affect problem solvability. No numerical errors were detected. We conclude that the translation quality is sufficient for our evaluation purposes.

A.2 Full Accuracy Tables

Table A.1: GSM8K Results by Model, Language, and Max Tokens

Llama-3.1-8B:

| Max Tokens | English | Chinese | ZH (translate-then-solve) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 128 | 4.6% (61/1319) | 6.8% (90/1319) | 0.2% (2/1319) |

| 256 | 59.9% (790/1319) | 49.8% (657/1319) | 39.0% (514/1319) |

| 512 | 80.4% (1060/1319) | 52.4% (691/1319) | 42.3% (558/1319) |

| 1024 | 79.6% (1050/1319) | 51.6% (680/1319) | 44.0% (580/1319) |

| 4096 | 80.3% (1059/1319) | 52.8% (697/1319) | 43.7% (576/1319) |

Qwen3-8B:

| Max Tokens | English | Chinese | ZH (translate-then-solve) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 128 | 13.8% (182/1319) | 17.1% (226/1319) | 32.5% (429/1319) |

| 256 | 69.5% (917/1319) | 70.7% (932/1319) | 86.8% (1145/1319) |

| 512 | 88.1% (1162/1319) | 90.7% (1196/1319) | 90.4% (1193/1319) |

| 1024 | 88.5% (1167/1319) | 89.8% (1185/1319) | 90.1% (1188/1319) |

| 4096 | 88.7% (1170/1319) | 89.4% (1179/1319) | 89.8% (1185/1319) |

Table A.2: Fine-tuned Llama-3.1-8B Results

| Model | English | Chinese | ZH (translate-then-solve) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Llama (base) | 80.3% (1059/1319) | 52.8% (697/1319) | 43.7% (576/1319) |

| Llama (ft-zh) | 81.1% (1069/1319) | 61.6% (812/1319) | 53.5% (705/1319) |

A.3 Token Length Analysis

Table A.3: ZH/EN Token Ratio by Tokenizer (GSM8K, Both Correct Only)

| Tokenizer | Samples | Avg EN Tokens | Avg ZH Tokens | ZH/EN Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qwen3-8B | 1,088 | 308.4 | 296.4 | 0.961 |

| DeepSeek-V3 | 1,088 | 288.4 | 258.9 | 0.898 |

| Seed-Coder-8B | 1,088 | 325.0 | 303.1 | 0.933 |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 1,088 | 294.1 | 303.7 | 1.033 |

| GPT-4o | 1,088 | 292.9 | 297.0 | 1.014 |

Table A.4: ZH/EN Token Ratio by Tokenizer (MMATH, Both Correct Only)

| Tokenizer | Samples | Avg EN Tokens | Avg ZH Tokens | ZH/EN Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qwen3-8B | 321 | 904.9 | 847.9 | 0.937 |

| DeepSeek-V3 | 321 | 823.6 | 748.3 | 0.909 |

| Seed-Coder-8B | 321 | 941.5 | 858.6 | 0.912 |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 321 | 860.1 | 813.3 | 0.946 |

| GPT-4o | 321 | 866.2 | 811.5 | 0.937 |

Note: Token ratios below 1.0 indicate Chinese uses fewer tokens than English for equivalent reasoning.

A.4 Fine-tuning Hyperparameters

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Base Model | meta-llama/Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct |

| Adaptation Method | LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) |

| LoRA Rank (r) | 32 |

| LoRA Alpha (α) | 64 |

| Target Modules | q_proj, k_proj, v_proj, o_proj, gate_proj, up_proj, down_proj |

| Learning Rate | 1e-5 |

| Max Steps | 500 |

| Batch Size | 1 |

| Gradient Accumulation Steps | 2 |

| Effective Batch Size | 2 |

| Precision | bfloat16 |

| Max Prompt Length | 512 tokens |

| Max Completion Length | 4096 tokens |

| Training Data | Chinese GSM8K train split (7,473 examples) |

Beltagy, I., Peters, M. E., & Cohan, A. (2020). Longformer: The Long-Document Transformer. arXiv:2004.05150. ↩

Zaheer, M., Guruganesh, G., Dubey, A., et al. (2020). Big Bird: Transformers for Longer Sequences. NeurIPS 2020. ↩ ↩2

Bolya, D., Fu, C.-Y., Dai, X., Zhang, P., Feichtenhofer, C., & Hoffman, J. (2023). Token Merging: Your ViT But Faster. ICLR 2023. ↩

Wei, Y., et al. (2023). Joint Token Pruning and Squeezing Towards More Aggressive Compression of Vision Transformers. CVPR 2023. ↩

Efficient Vision Transformer via Token Merger. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, 2023. ↩

Tay, Y., Dehghani, M., Bahri, D., & Metzler, D. (2022). Efficient Transformers: A Survey. ACM Computing Surveys. ↩

Kingma, D. P., & Welling, M. (2014). Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. ICLR 2014. ↩

Ballé, J., Laparra, V., & Simoncelli, E. P. (2017). End-to-end Optimized Image Compression. ICLR 2017. ↩

Liu, J., et al. (2023). Learned Image Compression with Mixed Transformer-CNN Architectures. CVPR 2023. ↩

Chen, T., et al. (2024). Variational Autoencoder-based Neural Network Model Compression. arXiv:2408.14513. ↩

Qwen Team. (2025). Qwen3-8B Model Card. Hugging Face. https://huggingface.co/Qwen/Qwen3-8B ↩

Meta AI. (2024). Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct Model Card. Hugging Face. https://huggingface.co/meta-llama/Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct ↩