Notes on C++ Syntax

Published:

Last updated: 2025-07-11

Very random notes on C++ syntax, mostly for my own reference. Does not follow any particular structure or order; just a hodgepodge of things I find useful or interesting.

1. & and &&, lvalue, rvalue and xvalue, std::move

Look at the following code snippet:

// The following use case comes from:

// https://github.com/NVIDIA/cutlass/blob/main/include/cute/atom/copy_atom.hpp#L398

template <class STensor>

CUTE_HOST_DEVICE

auto

partition_S(STensor&& stensor) const {

//static_assert(sizeof(typename remove_cvref_t<STensor>::value_type) == sizeof(typename TiledCopy::ValType),

// "Expected ValType for tiling SrcTensor.");

auto thr_tensor = make_tensor(static_cast<STensor&&>(stensor).data(), TiledCopy::tidfrg_S(stensor.layout()));

return thr_tensor(thr_idx_, _, repeat<rank_v<STensor>>(_));

}

There are a bunch of “strange” syntaxes that you would never see in plain C, or you’ve been using C++ only as “C with classes” or “C with STL”. We’ll break them down one by one, but first, let’s understand the meaning of & and && in C++.

Notes in advance: This section is pretty non-exhaustive and not that rigorous; if you want to see the exact definitions and use cases of lvalues, rvalues, xvalues, prvalues, and glvalues, please refer to Section 3 here. The examples below, however, should be good enough to illustrate the basic concepts.

&& stands for rvalue reference. But what are lvalues and rvalues?

- Lvalues: These are expressions that refer to a memory location, such as variables declared, array elements, or objects returned by reference from a function. They can be assigned a value.

- Rvalues: These are temporary, intermediate values. Examples include literals (like

42or3.14), the result of arithmetic operations (likex + y), or objects returned by value from a function. They cannot be assigned a value.

Correspondingly, C++ has two types of references:

- Lvalue references: Denoted by

&, they can bind to lvalues. For example,int& x = a;whereais an lvalue.

void print_and_modify(std::string& s) { // s is an lvalue reference

s += " World";

std::cout << s << std::endl;

}

int main() {

std::string my_string = "Hello"; // my_string is an lvalue

print_and_modify(my_string); // Works perfectly. my_string is now "Hello World"

// print_and_modify("Hello"); // ERROR! "Hello" is an rvalue literal.

}

But there is also a small exception to the rule: a const lvalue reference can bind to an rvalue.

void print_string(const std::string& s) { // s is a const lvalue reference

std::cout << s << std::endl;

}

int main() {

print_string("Hello"); // Works! "Hello" is an rvalue literal, but can bind to a const lvalue reference.

}

- Rvalue references: Denoted by

&&, they can bind to rvalues. For example,int&& x = 42;where42is an rvalue. The primary purpose is to enable move semantics. It allows a function to “steal” the resources (like heap-allocated memory) from a temporary object instead of performing a costly copy. This is a massive optimization for types that manage resources, likestd::stringorstd::vector.

void process_data(std::string&& s) { // s is an rvalue reference

// We can safely "move" from s, because we know it's a temporary.

std::string new_string = std::move(s); // we'll explain what is `std::move` soon

std::cout << "Moved string: " << new_string << std::endl;

}

int main() {

std::string my_string = "Hello"; // my_string is an lvalue

// process_data(my_string); // ERROR! my_string is an lvalue.

process_data("Temporary String"); // Works! "Temporary String" is an rvalue.

process_data(my_string + " World"); // Works! The result of the expression is an rvalue.

}

Apart from the lvalue and rvalue mentioned above, there are also xvalues (eXpiring values), which are a special kind of lvalue (strictly speaking, glvalue) that represents an object that is about to be moved from. They are typically the result of calling std::move() on an lvalue.

std::string my_string = "Hello"; // my_string is an lvalue

std::string&& xvalue = std::move(my_string); // my_string is now an xvalue

// Note that `&&` can bind to both rvalues and xvalues

Now here’s the question: what exactly is std::move? Its name is misleading in that it does not actually move anything. Instead, it simply takes an object (usually an lvalue with a name) and casts it to an rvalue reference. This is important because functions and constructors that are overloaded to accept an rvalue reference (&&) can then be called. These overloads are designed to be highly efficient by “stealing” or “moving” resources instead of copying them.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <utility> // Required for std::move

int main() {

// 1. We create a string. This is an lvalue.

// It allocates memory on the heap for its text.

std::string source = "This is a very long string that would be expensive to copy.";

std::cout << "Before move:\n";

std::cout << " source: \"" << source << "\"\n";

// 2. We use std::move to cast 'source' to an rvalue.

// This allows the move constructor of std::string to be called for 'destination'.

std::string destination = std::move(source);

// 3. Instead of copying the text, 'destination' just takes the internal pointers

// from 'source'. 'source' is now empty. This is extremely fast.

std::cout << "\nAfter move:\n";

std::cout << " destination: \"" << destination << "\"\n";

std::cout << " source: \"" << source << "\"\n"; // The source is now in a "valid but unspecified" state.

}

The result of the above code would be:

Before move:

source: "This is a very long string that would be expensive to copy."

After move:

destination: "This is a very long string that would be expensive to copy."

source: ""

Ta-da! By “moving” the string from source and “assigning” it to destination, we directly transferred the ownership of the string’s internal data from source to destination. source is still there, but it is now in a “valid but unspecified” state, meaning it can still be used, but its contents are no longer valid or meaningful.

Some people may be confused about why we use std::string destination = std::move(source); instead of std::string&& destination = std::move(source);. (You told me std::move returns an rvalue reference!) It’s pretty easy to get bewildered here, especially if you are coming from a C background. The key point is that std::move(source) indeed returns an rvalue reference, but we are NOT declaring a new variable here. What we want to do is to construct a new string object destination that takes ownership of the resources from source. So how come it can be done simply with an = operator, which we usually recognize as a naive “declaration” or “assignment” (like int x = 42; or x = x / 2)? To explain it, we would need to understand constructing and assigning objects in C++, which are explained in the next section.

2. Object Construction, Assignments, and Destruction

Constructing Objects

There are more ways to construct an object in C++ than you might think. Let’s start with a simple Widget class 1:

struct Widget {

int id;

std::string name;

// 1. Default Constructor

Widget() : id(0), name("Default") {

std::cout << "-> Default Constructor\n";

}

// 2. Parameterized Constructor

Widget(int i, std::string n) : id(i), name(std::move(n)) {

std::cout << "-> Parameterized Constructor (" << name << ")\n";

}

// 3. Copy Constructor

Widget(const Widget& other) : id(other.id), name(other.name) {

std::cout << "-> COPY Constructor (from " << other.name << ")\n";

}

// 4. Move Constructor

Widget(Widget&& other) noexcept : id(other.id), name(std::move(other.name)) {

other.id = -1; // Invalidate the moved-from object

std::cout << "-> MOVE Constructor (from " << name << ")\n";

}

// Destructor (called when the object is destroyed)

~Widget() {

std::cout << "<- Destructor (" << name << ")\n";

}

};

As you can see, we have defined four functions – all of which are named Widget, the same name as the class – and a ~Widget function, taking no parameters. These functions are not just regular functions when you give them the same name as the class: they are constructors (Widget) and a destructor (~Widget).

- Constructors are called when you create an object of the class;

- Destructors are called when the object is destroyed (e.g., goes out of scope or is explicitly deleted).

Also, you may notice there are more than one constructors, but they are distinguished by their different parameter lists. This is made possible by a feature called function overloading in C++, which we explain in full detail in Section 4. For now, the only thing you need to know is that C++ will choose the correct constructor based on the arguments we pass when creating an object. This also means that we can construct an object with multiple ways.

The four different constructors for the Widget class are called default constructor, parameterized constructor, copy constructor, and move constructor. Let’s go through each of them:

- Default Constructor: This is called when you create an object without any parameters. It initializes the object with default values. The syntax for a general default constructor is:

[Name]() : [Member1](value1), [Member2](value2) { /* body */ }

For those of you who are not familiar with the syntax, : [Member1](value1), [Member2](value2) is called an initializer list. It is basically equivalent to assigning values to the members of the class:

[Name]() {

[Member1] = value1;

[Member2] = value2;

/* body */

}

Calling it is straightforward:

Widget w1; // Calls the default constructor

To create an rvalue (temporary) object, simply use Widget(); would do. Rvalue objects are often used in contexts where you want to create an object without keeping a reference to it, such as when passing an object to a function that takes ownership of it.

Note: You CANNOT use the following way to call the default constructor, even though it looks like it should work by passing no parameters in the parentheses:

Widget w1();This is the so-called most vexing parse problem in C++. The above line is actually interpreted as a function declaration, not an object construction. It declares a function named

w1that takes no parameters and returns aWidget. To avoid the confusion, use the list initialization syntax (introduced at the end of this section) instead, or simply add nothing:Widget w1{};orWidget w1;.

- Parameterized Constructor: This constructor takes parameters to initialize the object with specific values. The syntax is similar to the default constructor, but it includes parameters:

[Name](Type1 param1, Type2 param2) : [Member1](param1), [Member2](param2) { /* body */ }

You can call it like this:

Widget w2(42, "MyWidget"); // Calls the parameterized constructor with id=42 and name="MyWidget"

Again, you can also create an rvalue object by using Widget(42, "MyWidget");.

So far so good, easy twisky. But sometimes, we want to create a new object based on an existing one (the case seen in Section 1). This is where the next two constructors come in:

- Copy Constructor: This constructor is called when you create a new object as a copy of an existing object. It takes a reference to the existing object as a parameter. The syntax is:

[Name](const [Name]& other) : [Member1](other.Member1), [Member2](other.Member2) { /* body */ }

You can call it like this:

Widget w3 = w2; // Calls the copy constructor, creating a new Widget with the same values as w2

Widget w4 = Widget(); // Calls the default constructor, then the copy constructor to create w4 as a copy of the default Widget

The = sign in Widget w3 = w2; is not just a simple assignment; it actually invokes the copy constructor to create a new object w3 that is a copy of w2.

Note that the copy constructor must take a const reference to the existing object. This is due to the reason we mentioned in section 1: an lvalue reference (&) can only bind to an lvalue, but a const lvalue reference can bind to both lvalues and rvalues. This allows the use case in Widget w4 = Widget();, where Widget() is an rvalue that can be bound to a const lvalue reference.

- Move Constructor: This constructor is called when you create a new object by “moving” the resources from an existing object. It takes an rvalue reference to the existing object as a parameter. The syntax is:

[Name]([Name]&& other) noexcept : [Member1](std::move(other.Member1)), [Member2](std::move(other.Member2)) { /* body */ }

You can call it like this:

Widget w5 = std::move(w2); // Calls the move constructor, transferring resources from w2 to w5

There are two important things to note here.

First, no more const in the parameter list, because what we’re doing here is exactly to “steal” the resources from the existing object–namely, we are going to modify the existing object.

Second, there’s a noexcept keyword in the declaration. noexcept is a promise you make to the compiler that your function will not throw an exception. If an exception is thrown from a noexcept function, the program immediately calls std::terminate and crashes. But why must we use noexcept? When the compiler is moving a block of memory, it can have two options: either copy the memory (using the copy constructor) or move the memory (using the move constructor). But moving is dangerous: if the move constructor halts in the middle of the operation, it can leave the object in an inconsistent state (some resources moved, some not). Therefore, compilers follow a rule in these scenarios:

- If your move constructor is

noexcept✅: The compiler knows the move operation cannot fail. It will confidently use your fast move constructor to move every element to the new memory location. - If your move constructor is NOT

noexcept❌: The compiler sees a risk and will play it safe. It will refuse to use your move constructor and fall back to the slower, but safer, copy constructor.

If you forget to mark your move constructor and move assignment operator as noexcept, you will lose the performance benefits of move semantics in many common situations, like when elements are rearranged inside a container. The compiler will choose to copy your objects instead of moving them.

There’s one sharp question that you might ask: after we’ve defined the move constructor, why do we still need to include the

constin copy constructor? You said that the reason why we useconstin the copy constructor is to allow binding to rvalues, but after the move semantics&&have been defined, there’s no longer such use cases, so why bother usingconst? The key lies in the backward compatibility. The move semantics were introduced in C++11, but the copy constructor has been around since the beginning of C++, so there are many old codebases where no move semantics are defined. Also, we want to make sure that there’s a fallback in case the move constructor does not work, such as when the object is not movable. Including aconstis a necessary insurance policy that allows the copy constructor to be used in those cases.

To sum up, the four constructors are used in different scenarios:

- Default Constructor: When you want to create an object with default values.

- Parameterized Constructor: When you want to create an object with specific values.

- Copy Constructor: When you want to create a new object as a copy of an existing object.

- Move Constructor: When you want to create a new object by transferring resources from an existing object.

They have different use cases and syntaxes, and are automatically followed by std::string, std::vector, and other STL containers. If you want to create your own class, you must define these constructors on your own. But different ways of constructing an object can sometimes be mixed and tricky. So there’s an additional syntax that can help you with that: list initialization, introduced in C++11. With only a pair of curly braces {}, it is now the preferred, “uniform” way to construct objects and can be used for almost every type of construction. The syntax is:

Widget w1{}; // Calls the default constructor

Widget w2{42, "MyWidget"}; // Calls the parameterized constructor with id=42 and name="MyWidget"

Widget w3{w2}; // Calls the copy constructor, creating a new Widget with the same values as w2

Widget w4{std::move(w2)}; // Calls the move constructor, transferring resources from w2 to w4

Assigning Objects

Constructing and assigning objects are two different things. When you construct an object, you create a new instance of the class. When you assign an object, you copy or move the values from one object to another existing object. Let’s take a second look at our Widget class, but this time, we add two additional functions: Widget& operator=(const Widget& other) and Widget& operator=(Widget&& other) noexcept. (For those of you who are not familiar with the syntax, operator= is also a special function in C++ that allows you to define how the assignment operator (=) works for your class. Almost all the operators in C++ can be overloaded, such as +, -, *, /, ==, !=, <<, >>, etc. We may cover them in a future section.)

struct Widget {

int id;

std::string name;

// 1. Default Constructor

Widget() : id(0), name("Default") {

std::cout << "-> Default Constructor\n";

}

// 2. Parameterized Constructor

Widget(int i, std::string n) : id(i), name(std::move(n)) {

std::cout << "-> Parameterized Constructor (" << name << ")\n";

}

// 3. Copy Constructor

Widget(const Widget& other) : id(other.id), name(other.name) {

std::cout << "-> COPY Constructor (from " << other.name << ")\n";

}

// 4. Move Constructor

Widget(Widget&& other) noexcept : id(other.id), name(std::move(other.name)) {

other.id = -1; // Invalidate the moved-from object

std::cout << "-> MOVE Constructor (from " << name << ")\n";

}

// 5. Copy Assignment Operator

Widget& operator=(const Widget& other) {

std::cout << "-> COPY assigning from " << other.name << "\n";

id = other.id;

name = other.name; // This is a deep copy for std::string

return *this;

}

// 6. Move Assignment Operator

Widget& operator=(Widget&& other) noexcept {

std::cout << "-> MOVE assigning from " << other.name << "\n";

id = other.id;

name = std::move(other.name); // Move the string's resources

other.id = -1; // Invalidate the moved-from object

return *this;

}

// Destructor (called when the object is destroyed)

~Widget() {

std::cout << "<- Destructor (" << name << ")\n";

}

};

- Copy Assignment Operator: This operator is called when you assign one object to another existing object. It takes a

constreference to the source object and copies its values into the current object. The syntax is:

[Name]& operator=(const [Name]& other) {

// Body of the function

// ... (copy values from `other` to `this`)

return *this; // Return a reference to the current object

}

You can call it like this:

Widget w1; // Calls the default constructor

Widget w2(42, "MyWidget"); // Calls the parameterized constructor

w1 = w2; // Calls the copy assignment operator, copying values from w2 to w1

Again, notice a const in the parameter list is necessary, because we want to allow the assignment of rvalues.

- Move Assignment Operator: This operator is called when you assign an rvalue to an existing object. It takes an rvalue reference to the source object and “steals” its resources, leaving the source object in a valid but unspecified state. The syntax is:

[Name]& operator=([Name]&& other) noexcept {

// Body of the function

// ... (move values from `other` to `this`)

return *this; // Return a reference to the current object

}

You can call it like this:

Widget w1; // Calls the default constructor

Widget w2(42, "MyWidget"); // Calls the parameterized constructor

w1 = std::move(w2); // Calls the move assignment operator, transferring resources from w2 to w1

w1 = Widget(100, "Temporary Widget"); // Also calls the move assignment operator, because `Widget(100, "Temporary Widget")` is an rvalue

Destructing Objects

When an object goes out of scope or is explicitly deleted, its destructor is called. The destructor is a special member function that cleans up the resources used by the object. The syntax is:

~[Name]() {

// Body of the destructor

// ... (clean up resources)

}

The destructor is automatically called when the object goes out of scope or is deleted. For example:

{

Widget w1; // Calls the default constructor

} // w1 goes out of scope, implicitly calls the destructor

Widget* w2 = new Widget(42, "MyWidget"); // Calls the parameterized constructor

delete w2; // Explicitly calls the destructor for w2, then frees the memory

If you don’t define a destructor, the compiler provides a default one that does nothing. However, if your class manages resources (like dynamic memory, file handles, etc.), you should define a destructor to release those resources.

Summary

Summarizing the above, we can conclude the so-called Rule of the Big Five. It states that if you write any one of the following, you should consider all five:

- Destructor (

~MyClass()): Cleans up resources when the object is destroyed. - Copy Constructor (

MyClass(const MyClass&)): Creates a new object as a copy of an existing object. - Move Constructor (

MyClass(Myclass&&) noexcept): Creates a new object by transferring resources from an existing object. - Copy Assignment Operator (

MyClass& operator=(const MyClass&)): Assigns values from one existing object to another. - Move Assignment Operator (

MyClass& operator=(MyClass&&) noexcept): Transfers resources from one existing object to another.

However, in modern C++, the best practice is to follow the Rule of Zero. This means you should avoid writing any of these functions unless absolutely necessary. Instead, rely on smart pointers (like

std::unique_ptrandstd::shared_ptr) and standard library containers (likestd::vector,std::string, etc.) that manage resources automatically. This way, you can avoid the complexity and potential pitfalls of manual resource management.

Answer to the Question in Section 1: Difference between std::string destination = std::move(source); and std::string&& destination = std::move(source);

After getting through all these, we can finally answer the question at the end of Section 1.

It becomes clear that std::string destination = std::move(source); is a construction of a new std::string object named destination, which is initialized by moving the contents of source. This means that destination will have its own copy of the data, and source will be left in a valid but unspecified state.

But what is std::string&& destination = std::move(source);? This is a declaration of a new rvalue reference named destination, which binds to the rvalue returned by std::move(source). This means that destination is not a new object, but rather a reference to the existing rvalue object, source, and it can be used to modify or access the data in source directly. Again, destination becomes a direct alias for source, and they are two different names for the exact same object in memory.

Now, it might be confusing to think that something that has a name, like destination or source, is an rvalue reference. C++ has a critical rule here: a named rvalue reference (like destination here) is treated as an lvalue in subsequent code, so using destination later (in construction or assignment) won’t trigger move semantics automatically. Think of it this way: something that has a name can be referred to over and over again throughout the code, so if the compiler really treats it as an rvalue and moves from it every time we use the name, it would be a disaster. Therefore, to enforce safety, C++ requires that you explicitly use std::move(destination) to indicate that you want to treat destination as an rvalue and trigger move semantics, even though destination is an rvalue reference. In practice, one would almost never use std::string&& destination = std::move(source); explicitly. The named rvalue reference is more commonly used for function overload resolution; by providing two versions of a function—one that takes an lvalue reference (&) and one that takes an rvalue reference (&&), you let the compiler automatically choose the correct and most efficient path based on the argument you provide. But after getting inside the function, the rvalue reference is treated as an lvalue, so you still need to use std::move() to trigger move semantics.

3. More on Lvalues, Glvalues, Rvalues, Prvalues and Xvalues

This section is kind of bookish and perhaps a bit too technical, but it provides a strict definition of the basic concepts – lvalues, rvalues, etc. – that we introduced in Section 1. You can safely skip this section if you are not interested in the details.

Historially, lvalues and rvalues go by their names because of the way they are used in expressions: lvalues appear on the left side, rvalues on the right side. For example, in the expression int x = 42;, x is an lvalue and 42 is an rvalue. This is not always the case, however, and does not count as the rigorous definition of lvalues and rvalues.

The following definitions and examples come from cppreference.

Strictly speaking, each C++ expression (an operator with its operands, a literal, a variable name, etc.) is characterized by two independent properties: a type and a value category. Each expression has some non-reference type, and each expression belongs to exactly one of the three primary value categories: prvalue, xvalue, and lvalue.

a prvalue (“pure” rvalue) is an expression whose evaluation

- computes the value of an operand of a built-in operator (such prvalue has no result object), or

initializes an object (such prvalue is said to have a result object).

The result object may be a variable, an object created by new-expression, a temporary created by temporary materialization, or a member thereof. Note that non-void discarded expressions have a result object (the materialized temporary). Also, every class and array prvalue has a result object except when it is the operand of

decltype.

Examples:

1. prvalues without result objects

// a. Prvalues without result objects

// a1. Literals

42; // prvalue of type int

3.14; // prvalue of type double

true; // prvalue of type bool

nullptr; // prvalue of type std::nullptr_t

// a2. Arithmetic operations

int x = 10;

int y = 20;

x + y; // The expression 'x + y' results in a prvalue (30).

// a3. Address-of operator

int x;

&x; // The address of x is a prvalue.

// a4. Logical and comparison operators

int a = 5, b = 10;

a < b; // prvalue of type bool (true)

a == b; // prvalue of type bool (false)

// a5. Function calls returning by value

int getValue() {

return 42;

}

getValue(); // The call to getValue() is a prvalue of type int.

// a6. Lambda expressions

[](){}; // This is a prvalue. More on lambda expressions in later sections.

2. Prvalues with result objects

// b. Prvalues with result objects

// b1. Variable initialization

int x = 42; // 42 is a prvalue used to initialize x. x is the result object.

std::string s = "hello"; // "hello" is used to create a temporary std::string,

// which is a prvalue that initializes s.

// b2. Objects created by `new`

int* p = new int(10); // The new-expression creates an int, and `10` is a prvalue

// used for its initialization. The allocated int is the result object.

// b3. Temporary materialization: when a prvalue needs to have a lifetime beyond the current

// expression, a temporary object is created. This is called temporary materialization.

const int& ref = 42; // 42 is a prvalue. To bind it to a const lvalue reference,

// a temporary int object is created and initialized with 42.

// This temporary is the result object.

struct MyType { int x; };

MyType().x; // MyType() is a prvalue. To access its member 'x', a temporary

// object of type MyType must be created. This temporary is the result object.

// b4. Initializing a member of an object

struct Point { int x, y; };

Point p = {10, 20}; // {10, 20} is a prvalue of type Point that initializes p.

// More specifically, 10 and 20 are prvalues that initialize

// the members x and y. The members p.x and p.y are the result objects.

- an xvalue (an “eXpiring” value) is a glvalue that denotes an object whose resources can be reused. Here, a glvalue (“generalized” lvalue) is an expression whose evaluation determines the identity of an object or function.

- an lvalue is a glvalue that is not an xvalue.

Examples:

1. Result of std::move or a static_cast to an rvalue reference is an xvalue:

std::string s = "hello"; // 's' is an lvalue

std::string s2 = std::move(s); // The expression `std::move(s)` is an xvalue.

// It refers to the object 's', but signals

// that its resources (the allocated string data)

// can be moved. 's' is left in a valid but

// unspecified state.

int x = 42;

int&& rref = static_cast<int&&>(x); // `static_cast<int&&>(x)` is an xvalue.

2. Result of a function returning an rvalue reference is an xvalue:

#include <utility>

#include <vector>

template<typename T>

T&& my_forward(T& param) {

return std::move(param); // The return expression here results in an xvalue

}

int main() {

std::string str = "world";

std::string str2 = my_forward(str); // The call `my_forward(str)` is an xvalue.

}

If you are not familiar with templates, read Section 5.

3. Member Access on an xvalue is an xvalue:

struct Point { int x, y; };

Point p{10, 20};

int x_coord = std::move(p).x; // `std::move(p)` is an xvalue of type Point.

// `std::move(p).x` is an xvalue of type int.

// This moves the value of p.x into x_coord.

- an rvalue is a prvalue or an xvalue.

With the defitions above, we can now define what & and && mean in C++:

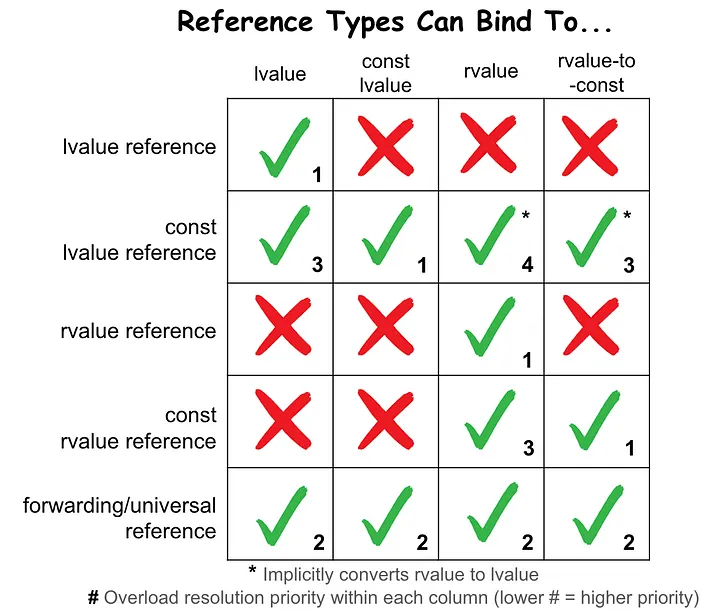

&denotes an lvalue reference. An lvalue reference can bind to lvalues, but not to prvalues or xvalues.&&denotes an rvalue reference. An rvalue reference can bind to prvalues and xvalues, but not to lvalues.

(1) What does it mean to “bind” to a value? In C++, binding simply means creating a reference to an object or value. It is exactly the process when you declare

int& x = 42;orint&& y = std::move(x);: you are binding the namexoryto the value42or the rvalue reference returned bystd::move(x). Binding a reference to an object does not mean that the reference itself belongs to the same value category as the object. Expressionxandyare both lvalues, even thoughxis an lvalue reference andyis an rvalue reference. 2(2) C++ has some additional rules for the

constqualifier.

- A non-const lvalue reference can only bind to non-const lvalues.

- A const lvalue reference can bind to all value categories, including const and non-const lvalues, prvalues, and xvalues. This is the most flexible type of reference, because it promises not to modify the object it refers to. The lifetime of the temporary object created by binding a rvalue to a const lvalue reference is extended to the lifetime of the reference. 3

- A non-const rvalue reference can only bind to non-const prvalues and xvalues.

- A const rvalue reference can bind to both const and non-const prvalues and xvalues, but not to lvalues.

Here’s an overall example that summarizes the above concepts:

#include <type_traits>

#include <utility>

template <class T> struct is_prvalue : std::true_type {};

template <class T> struct is_prvalue<T&> : std::false_type {};

template <class T> struct is_prvalue<T&&> : std::false_type {};

template <class T> struct is_lvalue : std::false_type {};

template <class T> struct is_lvalue<T&> : std::true_type {};

template <class T> struct is_lvalue<T&&> : std::false_type {};

template <class T> struct is_xvalue : std::false_type {};

template <class T> struct is_xvalue<T&> : std::false_type {};

template <class T> struct is_xvalue<T&&> : std::true_type {};

int main()

{

int a{42};

int& b{a};

int&& r{std::move(a)};

// Expression `42` is prvalue

static_assert(is_prvalue<decltype((42))>::value);

// Expression `a` is lvalue

static_assert(is_lvalue<decltype((a))>::value);

// Expression `b` is lvalue

static_assert(is_lvalue<decltype((b))>::value);

// Expression `std::move(a)` is xvalue

static_assert(is_xvalue<decltype((std::move(a)))>::value);

// Type of variable `r` is rvalue reference

static_assert(std::is_rvalue_reference<decltype(r)>::value);

// Type of variable `b` is lvalue reference

static_assert(std::is_lvalue_reference<decltype(b)>::value);

// Expression `r` is lvalue

static_assert(is_lvalue<decltype((r))>::value);

}

To be honest, the above definitions are quite complicated, obscure, and not at all intuitive. I can’t say I fully understand them, but I hope they provide a broader perspective on the value categories in C++. For those who are interested in a more detailed and rigorous explanation, I recommend reading the entire cppreference page on value categories.

4. Functions, Functors, and Lambda Expressions

To begin with, I’d like to sincerely apologize for possible occurrences of my misusing the term “object” in previous sections. We know that in Python everything is an object. In C++, however, the term “object” has a more specific meaning: it is used to specifically refer to instances of classes or structs.

Functions are not objects in C++, unlike in Python. They are just bunches of code that can be executed when called. If we trace down to the assembly level, we can see that functions are just a sequence of instructions that are given a label (the function name) and can be jumped to when called. This means that we can’t pass functions around like we do in Python, return functions within functions, or assign them to variables. C++ functions are more than that, of course; one significant feature is that they can be overloaded.

Function Overloading

In Python, a function can be repeatedly defined with the same name, but every time we redefine the function with the same name, it will immediately point to the newer version (namely, overwrite the older definitions). In C++, however, you can have multiple functions with the same name as long as they have different parameter lists, and the compiler automatically chooses the correct function to call based on the arguments you provide. This is called function overloading.

#include <iostream>

void print(int i) {

std::cout << "Printing an int: " << i << std::endl;

}

void print(double d) {

std::cout << "Printing a double: " << d << std::endl;

}

int main() {

print(10); // Calls the int version

print(3.14); // Calls the double version

}

<NOT COMPLETED! To be continued…>

5. Type Deduction, auto, decltype, and Templates

Go back to the script in Section 1.

// The following script comes from:

// https://github.com/NVIDIA/cutlass/blob/main/include/cute/atom/copy_atom.hpp#L398

template <class STensor>

CUTE_HOST_DEVICE

auto

partition_S(STensor&& stensor) const {

//static_assert(sizeof(typename remove_cvref_t<STensor>::value_type) == sizeof(typename TiledCopy::ValType),

// "Expected ValType for tiling SrcTensor.");

auto thr_tensor = make_tensor(static_cast<STensor&&>(stensor).data(), TiledCopy::tidfrg_S(stensor.layout()));

return thr_tensor(thr_idx_, _, repeat<rank_v<STensor>>(_));

}

Yes, we have seen what is && in STensor&& stensor: indicating an rvalue reference, you should say. With this in mind, let’s look at a real use case of such partition_S function. Note in advance that partition_S is a member function of the class ThrCopy4.

// The following script is adapted from:

// https://github.com/NVIDIA/cutlass/blob/a1aaf2300a8fc3a8106a05436e1a2abad0930443/include/cutlass/gemm/collective/sm70_mma_twostage.hpp#L192

template <class Tensor>

CUTLASS_DEVICE void

operator() (Tensor g, int thread_idx)

{

using namespace cute;

ThrCopy gmem_tiled_copy;

auto copy_thr = gmem_tiled_copy.get_slice(thread_idx);

Tensor tg = copy_thr.partition_S(g);

// ... other parts omitted ...

}

In this example, partition_S takes the parameter g as the input. However, g is a class Tensor object, and is inevitably an lvalue. So how can we pass it to partition_S, which requires an rvalue reference? Is this script wrong?

Short answer: NO. The function signature template <class STensor> auto partition_S(STensor&& stensor) uses what is known as a forwarding reference (or universal reference), not a strict rvalue reference, and this concept is tied closely to another feature named type deduction in C++, which we will examine in this section.

Templates

Templates are one of the most fascinating features of C++, and we have already seen a glimpse of them through many examples in this note. They are actually super intuitive: when you define a template, you are essentially creating a whole bundle of functions/classes that are inherently the same, but associated with different types.

For instance, suppose we want to create a function that adds three numbers together. In Python, we can simply write:

def add3(a, b, c):

return a + b + c

It works for any type of a, b, and c as long as they support the + operator. However, this is not allowed in C++, for C++ is a statically typed language, meaning that the types of variables must be known at compile time. Sadly, we have to write different functions for each possible type (double, int, float, etc.):

int add3(int a, int b, int c) {

return a + b + c;

}

double add3(double a, double b, double c) {

return a + b + c;

}

float add3(float a, float b, float c) {

return a + b + c;

}

These functions are actually the same. The only difference is their parameter types. So why not just write a single function that can accept any type? This is where templates come in. We can define a template function like this:

template <typename T> // or equivalently, template <class T>

T add3(T a, T b, T c) {

return a + b + c;

}

T is a template parameter that will be deduced by the compiler based on the types of the arguments actually passed to the function. When you call the function, you can simply write:

add3(1, 2, 3); // Compiler deduces T = int

add3(1.5, 2.7, 3.2); // Compiler deduces T = double

The above examples are quite straightforward. However, you may start to wonder the edge cases – and yes, there are cases where you might need to explicitly specify the template parameter. The general syntax for calling a template function is function_name<template_parameter>(arguments):

add3<double>(1, 2, 3); // Forces double arithmetic with int arguments

add3<int>(1.1, 2.2, 3.3); // Forces int arithmetic (truncates the doubles)

// This would be an error because the compiler can't decide between int and double:

// add3(1, 2.5, 3); // Error! Mixed types

add3<double>(1, 2.5, 3); // OK - explicitly specify double to resolve ambiguity

Not limited to functions, templates can also be used to define classes. For example, we can define a simple Pair class that holds two values of the same type:

template <typename T>

class Pair {

public:

T first;

T second;

Pair(T a, T b) : first(a), second(b) {}

void print() {

std::cout << "Pair(" << first << ", " << second << ")\n";

}

};

We can then create pairs of different types:

Pair intPair(1, 2); // C++17 and later

Pair doublePair(1.5, 2.5);

Pair<std::string> stringPair("Hello", "World");

Note: Before C++17, all template parameters for template classes must be specified explicitly even if they can be deduced; for instance,

Pair<int> intPair(1, 2);is required. Since C++17, thanks to class template argument deduction (CTAD), we can omit the template parameters when creating an object of a template class, as long as the compiler can deduce them from the constructor arguments.

Sometimes, we may want to define a generic function/class that works mostly the same for all types, but with some special behavior for certain types. C++ provides a way to do this using template specialization. For example, to compare two values of the same type, we can define a generic compare function while providing a specialized version for C-style const char* strings:

#include <cstring>

template <typename T>

bool is_equal(T a, T b) {

return a == b; // Generic comparison

}

template <>

bool is_equal(const char* a, const char* b) {

return std::strcmp(a, b) == 0; // Specialized comparison for C-style strings

}

The syntax template <> indicates that we are providing a specialization for the template function. Compiler will first try to match the specialized version, before falling back to the generic version if no match is found.

Type Deduction

Undoubtedly, deducing the type of a template parameter is crucial for the functionality of templates. The general rules that govern type deduction in C++ are as follows:

- Parameters passed by value (

func(T arg)): The compiler ignores anyconst,volatile, or references. It essentially copies the argument.

template <typename T>

void func(T arg);

const int x = 42; // x is of type const int

const int& rx = x; // rx is of type const int&

func(x); // T deduced as int

func(rx); // T deduced as int

In the example above, both x and rx are deduced as int in func; the const is ignored.

Note: Pointer cases are a bit more complicated: only the highest level

constorvolatile(the cv-qualifiers of the pointer itself) is ignored.template <typename T> void func(T arg); const int x = 42; const int* px1 = &x; int const* px2 = &x; int* const px3 = &x; const int* const px4 = &x; func(px1); // T deduced as const int* func(px2); // T deduced as const int* func(px3); // T deduced as int* func(px4); // T deduced as const int*For those of you who aren’t familiar with

const,const intis the same asint const;const int*represents a pointer to aconst int, whileint* constrepresents aconstpointer to anint, and they are different.const int* const, as you may have guessed, is aconstpointer to aconst int. The firstconstapplies to the type pointed to, while the secondconstapplies to the pointer itself.

- Parameters passed by lvalue references or pointers (

func(T& arg)orfunc(T* arg)): The compiler keeps the cv-qualifiers but omits the reference, pointer, or the cv-qualifiers of the pointer itself. This can be understood as the compiler tries to find a proper typeT, such thatT&orT*can bind to the argument type. For instance, if you pass aconst int&orconst int*to a function that takesT&orT*, the compiler deducesTasconst int. If you simply pass anint, the compiler deducesTasint, sinceint&can bind to anint.

template <typename T>

void func(T& arg);

template <typename T>

void func(T* arg);

const int x = 42; // x is of type const int

const int& rx = x; // rx is of type const int&

const int* const px = &x; // px is of type const int* const

int* p = const_cast<int*>(&x); // p is of type int*

int& r = const_cast<int&>(rx); // r is of type int&

func(x); // T deduced as const int

func(rx); // T deduced as const int

func(px); // T deduced as const int

func(p); // T deduced as int

func(r); // T deduced as int

- Parameters passed by rvalue references (

func(T&& arg)): This is a special case of type deduction known as forwarding references (or universal references). It can also accept all possible value categories, just likeconst T&, and it only applies to template functions.

Both classes and structs are referred to as classes in this note. The only difference between them is that structs have public members by default, while classes have private members by default. ↩

I know this section is ordered in a bad way. It would probably be better if I could clarify these concepts at the very beginning. Maybe I will revise the entire section in the future. ↩

Historically, lvalue references were introduced in C++98 before rvalue references (C++11). Often time we prefer defining a function that takes lvalue references as its arguments, instead of by values or pointers, because it could save us from unnecessary copies while treating the argument as the original object. For instance, we could define a function

int processWidget(Widget& w)that processes the data of aWidgetobject without copying it. However, this function only accepted lvalues, meaning we couldn’t pass a temporary object (an rvalue) to it, such asprocessWidget(Widget()). This would be a big headache, so Bjarne Stroustrup brought up the idea of allowingconstlvalue references to bind to all possible values, including rvalues. The logic was if a reference promises not to modify the object (const), then it should be perfectly safe to bind it to a temporary object. There’s no danger in modifying a temporary if you’ve promised not to modify it in the first place. Now, we can define the function asint processWidget(const Widget& w)and we’re all set. After C++11, we can directly bind rvalues to rvalue references, but the oldconstlvalue reference still exists and is widely used in C++ codebases. (I just realized that such explanation overlaps with what we’ve introduced in Section 2. I’ll reorganize the content someday to avoid redundancy. SORRYY!) ↩Simplified; the actual

ThrCopyclass is a more complicated template class. Here we simply aim to demonstrate the use ofpartition_Sfunction. ↩